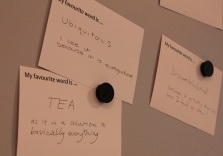

A trip to the Oxford University Press museum a few weeks ago spurred on some thoughts about favourite words – surely a true lingthusiast has a good favourite word or two? The thing is there are just too many great words to choose from. When we’re pushed to choose, it does seem that the ones that make it to the top of the list are the ones that roll off the tongue the most, such as mellifluous or ubiquitous. But one great word suggestion that is not only fun to say but actually has an interesting word story too is quintessential.

You wouldn’t think there would be anything particularly remarkable about the origin of quintessential; looking at it, it looks quite French and you can see how it can break down into essential and then, presumably, essence. But what about the quint part?

Think quintet or quintuplets. Quintessence literally means the ‘fifth essence’. Going back (via Medieval French) to Latin, as quinta essentia, it was used in classical and medieval philosophy to refer to:

A fifth substance in addition to the four elements, thought to compose the heavenly bodies and to be latent in all things.

(oxforddictionaries.com)

It was introduced to philosophical theory by Aristotle and entered Latin via a loan translation (ie the literal construction of ‘fifth element’ was borrowed) of the Greek pempte ousia. The basic idea was that there are five elements that made up all matter: fire, earth, air, water and quintessence. The first four we’re already familiar with but quintessence, also known as aether, was thought to make up the heavenly bodies and the rest of the universe. It was used to explain several natural phenomena, including gravity and the motion of light.

Over time, our scientific knowledge evolved and the theory of the five elements was dismissed but quintessential stuck on in there by hanging on to that last part of its meaning – ‘latent in all things’ – so that it eventually came to mean ‘the intrinsic and central constituent of something’ or ‘the most perfect or typical example’.

e publishing giant with an extensive history, the OUP is important to us language fans because of the

e publishing giant with an extensive history, the OUP is important to us language fans because of the